| Article ID | Journal | Published Year | Pages | File Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9089459 | Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine | 2005 | 4 Pages |

Abstract

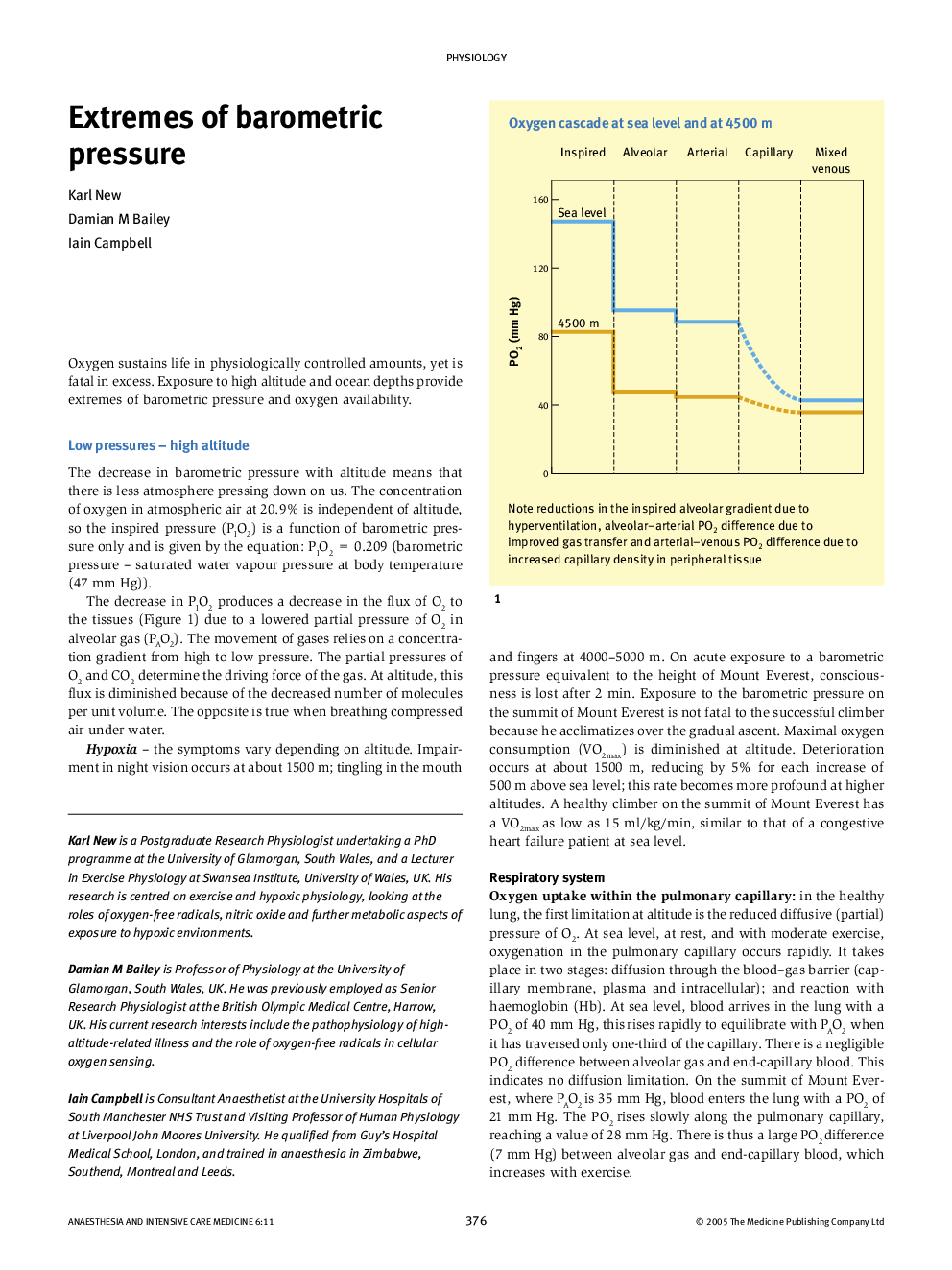

Oxygen sustains life in physiologically controlled amounts, yet is fatal in excess. Exposure to high altitude and ocean depths provide extremes of barometric pressure and oxygen availability. At altitude, the percentage oxygen in the atmosphere is the same as at sea level but the partial pressure of oxygen is reduced, thus reducing the oxygen gradient between the atmosphere and the cells. Failure to adapt, or too rapid exposure to altitude, can produce acute mountain sickness, manifest in its most extreme forma as pulmonary or cerebral oedema. Adaptations occur by an immediate increase in ventilation. This increase rises further during the first few days at altitude as readjustment occurs in the CSF (and thus the respiratory centre), pH and bicarbonate concentrations, increasing the sensitivity of the respiratory centre to the partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Improvements are seen in the ventilation/perfusion relationships, brought about by hypoxic vasoconstriction and an increase in pulmonary artery pressure. Haemoglobin concentrations increase and in the periphery there is an apparent increase in capillary density. Diving presents a physiological challenge in terms of external pressures on the lung and other gas spaces, and the effects that increased partial pressures of oxygen and nitrogen have on cell function. Oxygen is toxic in excess and nitrogen produces confusion and narcosis. For prolonged exposure to high pressures it is normal practice to replace the nitrogen in the gases breathed with helium, because of its relative insolubility, and to reduce the concentration of oxygen. Rapid ascent can cause barotrauma to the lungs; nitrogen may come out of solution in the circulation and cause tissue damage.

Keywords

Related Topics

Health Sciences

Medicine and Dentistry

Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

Authors

Karl New, Damian M Bailey, Iain Campbell,